The story is long, complex and sorry. I can't pretend to understand it fully. Now the debt has to be understood as a political quantity, not a simple heap of euros. Economics used to be called 'political economics' - it seems to me a great deal of damage has been done by the divorce, when economics tried to become a mathematical instead of a social science.

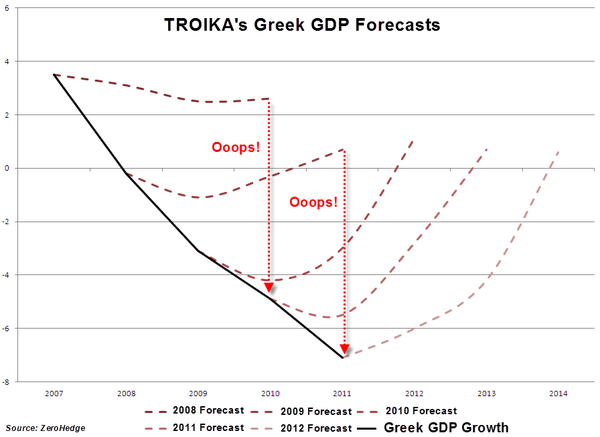

There seem to be no innocent parties except perhaps the poor and new poor of Greece, driven to suicide, dying for lack of medication, starving quietly. However the profligacy and corruption of the previous governments caused only debt: whereas the austerity imposed by the Troika, in defiance of common sense and elementary economics, has immiserated the country and punished the innocent. The Troika has had five years of austerity which has utterly failed by every metric conceivable, even their own forecasts. Via Felix Salmon on Twitter, here they are.

Notice how as the situation gets worse, so the forecasts detach further and further from reality.

Syriza has had five months of desperate fighting in a rearguard action to preserve its country and people. After these five months, the Troika decided the best bet would be to propose a deal that would discredit Syriza and render them unable to govern. As a bonus, this deal would enforce the austerity policies that have been failing for five years, and guarantee more needless deaths.

Some extracts follow. I particularly like the morality tales of the first one.

Yes, the Greek state was an unworthy and sometimes unscrupulous

debtor. Newsflash: The world is full of unworthy and unscrupulous entities

willing to take your money and call the transaction a “loan”. It always will

be. That is why responsibility for, and the consequences of, extending credit

badly must fall upon creditors, not debtors. There is one morality tale that

says the debtor must repay, or she has sinned and must be punished. There is

another morality tale that says the creditor must invest wisely, or she has

stewarded resources poorly and must be punished. We get to choose which morality

tale we most use to make sense of the world. We do, and surely should, use both

to some degree. But if we emphasize the first story, we end up in a world full

of bad loans, wasted resources, and people trapped in debtors’ prison,

metaphorical or literal. If we emphasize the second story, we end up in a world

where dumb expenditures are never financed in the first place.

Pre 2009, financial markets were happy to hold Greek sovereign debt

at rates not much above German. Either

(1) financial markets reliably aggregate all available information,

in which case the Greek government was correct to trust their judgement that

its borrowing was cheap and sustainable, and was subsequently the victim of an

unforeseeable shock. Or else

(2) financial markets do not send reliable signals about social

costs and the probabilities of future states of the world. In which case, the

commitment of the euro system to maximum freedom of financial flows is

fundamentally flawed and will inevitably produce crises.

I don’t think there’s any way, even in principle, to tell a story

in which the Greek debt crisis is mainly attributable to the actions of the

Greek government.

Philippe: Nobody denies Greek governments were profligate. But reckless borrowers require reckless lenders. It is those reckless private creditors who were bailed out by eurozone governments and the International Monetary Fund in 2010: nine of every ten euros lent to an insolvent Greece since then went to pay back debt that should have been restructured. Because of eurozone governments’ refusal to accept a restructuring of Greece’s debts in 2010, the austerity subsequently imposed and the depression that this caused were unnecessarily great – perversely causing public debt to soar as a share of Greece’s shrivelled GDP. One quarter of positive growth after a collapse of GDP of 21 per cent over five years – a cumulative loss of more than 100 per cent of Greek output – scarcely vindicates the creditors’ strategy.

Update: ex-finance minister Varoufakis on the deal of July 13:

‘This has nothing to do with economics. It has nothing to do with putting Greece on the way to recovery. This is a new Versailles Treaty that is haunting Europe again, and the prime minister knows it. He knows that he’s damned if he does and he’s damned if he doesn’t.’

‘In the coup d’état the choice of weapon used in order to bring down democracy then was the tanks. Well, this time it was the banks. The banks were used by foreign powers to take over the government. The difference is that this time they’re taking over all public property.’

‘In parliament I have to sit looking at the right hand side of the auditorium, where 10 Nazis sit, representing Golden Dawn. If our party, Syriza, that has cultivated so much hope in Greece ... if we betray this hope and bow our heads to this new form of postmodern occupation, then I cannot see any other possible outcome than the further strengthening of Golden Dawn. They will inherit the mantle of the anti-austerity drive, tragically.

The project of a European democracy, of a united European democratic union, has just suffered a major catastrophe.’